To prepare for our nation’s 250th anniversary, I have been reading Benson Bobrick’s “Angel in the Whirlwind: The Triumph of the American Revolution.” At 495 pages, it’s taking awhile to finish—and it is not a book to hurry through. Maybe it’s the season of life, or just a heightened sense of appreciation for the abundance and blessedness of life in this country, but I find myself continually moved by the dogged, persevering, sacrificial spirit of our country’s founding populations. True, as tensions rose between the colonies and Britain, there were many loyalists to the Crown, but the patriots would not—would not—relent.

The genius of the incredibly well-educated—and may I add, biblically grounded—men who gathered in Philadelphia, and the patient, deliberate way they went about their task laid the groundwork for the rights and privileges we now enjoy as citizens of the United States. That was, however, just the beginning. The war that followed was, for many, many months, one of loss and retreat and great suffering. But Washington and his generals and the ill-equipped men they commanded, against all odds, triumphed.

I am thinking about them in this season with a thankful heart.

I am also thinking about the remarkable folks who started it all. It has been four years since I last published this post and, rereading it recently, I have decided to publish it again. Our country has a story never equaled in all of history. We should never, ever forget it.

““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““““`

All great and honorable actions are accompanied with great difficulties and must be overcome with answerable courages. William Bradford, governor of Plymouth colony, age 30

What kind of people would leave their homes, property, families, histories, get on a small ship, and set sail for the horizon? A very particular kind of people, for sure. This Thanksgiving is a good time to turn our minds from political discord and remember the very early courage and sacrifice at the heart of our nation’s beginnings. There is much to appreciate:

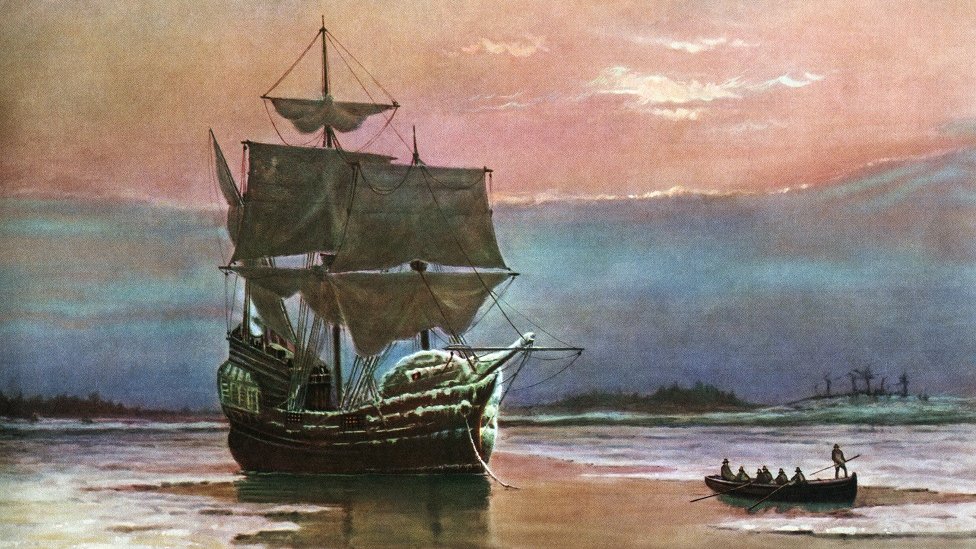

I admire their determination. Admittedly, the Puritans had a pretty severe view of righteous living. They endured scorn, financial pressure, and outright persecution from their fellow English citizens. Relocating to Holland, they eventually found financial backing to head for the New World. Their undertaking has been described as audacious and risky which, in light of what they were to endure, is an understatement. On September 16, 1620, 102 of them boarded the 90 foot long Mayflower. They disembarked at Plymouth on December 16th at the start of a bitter winter. Answerable courages, indeed.

I admire their motives. Before they set sail, William Bradford described their objectives. They had ” . . . a great hope . . . of laying some good foundation . . . for the advancing of the Gospel of the Kingdom.” Other groups did have more mercenary aims. But the Pilgrims’ primary focus was freedom to worship, and sharing the Gospel with native tribes—the rampant, modern-day rewriting of American history notwithstanding.

I admire their foresight in drawing up and signing the Mayflower Compact while still on board ship. It provided an orderly way of establishing the colony. They didn’t just land at Plymouth and head off willy-nilly doing their own thing. Its premise, by the way, was that government rests on the consent of the governed, a theme that initiated the parting of ways between the colonies and the Crown 150 years later.

I admire their fortitude. Nearly half of the settlers died during that first terrible winter of 1620-1621.

I admire their treaty of peace and mutual support with the local Wampanoag tribe. It was signed the following spring and read in part:

That he nor any of his should do hurt to any of their people.

That if any of his did hurt any of theirs, he should send the offender, that they might punish him.

That if anything were taken away from any of theirs, he should cause it to be restored; and they should do the like to his.

If any did unjustly war against him, they would aid him; if any did war against them, he should aid them.

This clear, simple, Old Testament-flavored treaty lasted for more than 50 years. You have to admire that. A lot.

And, of course, I admire their first harvest celebration, now known as Thanksgiving. The menu included:

- deer

- duck

- geese

- turkey

- clams

- eel

- fish

- wild plums

- leeks

- cornbread

- watercress

- corn

- squash – and other veggies, maybe.

I like the idea of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag celebrating together around the table, followed by games and dancing. Sugar was, tragically, probably not available, so it was unlikely that pie made an appearance. But with that menu, who would notice?

That first Thanksgiving was preceded by terrible suffering and followed by yet more difficulties—and answerable courages. We owe them a lot, that first hardy band of settlers. With my precious family, I will be thanking the Lord for them again at our beautiful, blessed, bountiful table.

I hope you will, too.